Tuesday, January 03, 2017

Epilogue: Ten Years Later a Mangleboard begins!

It has been 10 years since I had my research trip to Norway. By chance, I have been invited to participate in an exhibit at The Center for Art in Wood in 2017 (Philadelphia): Mangle Boards and Reflections. This is an iconic Nordic folk art form that I first encountered in my own field studies. I am delighted to be embarking on this new project from halfway across the world as I now live in Australia.

My inspiration comes from a myriad of source materials as usual, but I will be drawing on the tradition as it has been beautifully detailed in the new publication by Jay Raymond: Mangle Boards of Northern Europe. http://streamlinedirons.com/index.php

My inspiration comes from a myriad of source materials as usual, but I will be drawing on the tradition as it has been beautifully detailed in the new publication by Jay Raymond: Mangle Boards of Northern Europe. http://streamlinedirons.com/index.php

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

Outside Trondheim: Orkanger and Kvåle, August 15

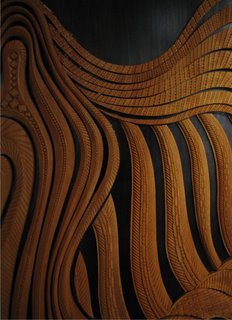

Kjell Eriksmoen arranged another excellent field trip outside of Trondheim. His neighbor, Arne, was our unofficial tour guide for the day. As a result of not inheriting a cabinet which he was particularly admired, Arne has become an expert on a local style of carved wooden cabinets, Orkdalskap. Orkanger is southwest of Trondheim by about half and hour by car. First we went to an old hotel near Orkanger, Bordshaug. There is one particular room in this hotel, once a private residence, that was commissioned and built around 1904. The wood panneling and cabinets that line the room are intricately carved in this local style, a verion of the Norwegian accanthus carving that I learned about in Lillehammer.

After visiting the hotel, we went to visit a local wood carved-furniture maker who has continued with this style. Mr. B. Kvåle is about 80 years old and says he has been in the woodshop everyday since he was 15 years old (so he knows what he is doing!). He has learned woodworking in the most traditional way, passed from father to son with no formal woodworking schools. Mr. Kvåle showed me an old photo of a group of men. It was a class photo from a very short course in woodworking, and both his father and grandfather were in the picture. He has passed this unique craft along to his own son, Olav. Olaf was at the house when we were there, and we were going to see him at his place later in the day.

In the meantime, Kjell, Arne, and I proceeded to visit another woodworker, Kjell Fannrem. Kjell has made all of the furniture in his house, including some variations on traditional Norwegian tall cabinets that are decorated with a mosaic/inlay of cross-sections of yew branches rather than with traditional carving. Kjell says that this embellishment took as long as the cabinet itself. Most of what Kjell does is making small boxes and baskets using traditional bentwood and sveiping, that is the stiching with birch roots that I first learned about in Voss. He is able to sell these at a local market that allows only local items made by hand. Kjell demonstrated sveiping to us and let me have a short length of birch root to play with back in the shop. To get the birch root myself I would have to go to a bog in the spring and dig it up.

After this visit, we went out of the town and up in to the mountains to find Olav Kvåle. Olav met us at the bottom of his steep and rough gravel road, where we transferred into his jeep. Olav is living a woodsman´s life in the forest. On the property, which has been in the family since around 1875, there are several small lafted cabins. The main house has been there for many years, and his parents always used it as a summer cabin, but since Olav moved up there in 1975, he has bought some other lafted cabins from other places and put them on the property. He says that it only takes about 3 hours to disassemble a lafted cabin, and about one day to reassemble it.

Olav is doing all of his carving in this place using hand tools and a little bit of router work. He has a small hydro and some solar pannels giving him power. Right now, he goes down to his father´s shop to use the machines for building the cabinets, but he is installing a generator so that he can eventually move the machines up to this mountain property. When there is snow, he is skiing in and out of the property. Olav lives by himself but often has guests and takes interns for several weeks at a time. Olav may well be the only person continuing to make this Orkdalskap right now. He has trained one German woman, and another from the Midwetern United States. Hopefully more woodworkers will visit him and carry on this tradition.

We had a very good afternoon relaxing with the Kvåles in the main house. I had some Norwegian moonshine in my coffee, the preferred mix. The moonshine is kept in a jug in the case of the grandfather clock for full effect.

After visiting the hotel, we went to visit a local wood carved-furniture maker who has continued with this style. Mr. B. Kvåle is about 80 years old and says he has been in the woodshop everyday since he was 15 years old (so he knows what he is doing!). He has learned woodworking in the most traditional way, passed from father to son with no formal woodworking schools. Mr. Kvåle showed me an old photo of a group of men. It was a class photo from a very short course in woodworking, and both his father and grandfather were in the picture. He has passed this unique craft along to his own son, Olav. Olaf was at the house when we were there, and we were going to see him at his place later in the day.

In the meantime, Kjell, Arne, and I proceeded to visit another woodworker, Kjell Fannrem. Kjell has made all of the furniture in his house, including some variations on traditional Norwegian tall cabinets that are decorated with a mosaic/inlay of cross-sections of yew branches rather than with traditional carving. Kjell says that this embellishment took as long as the cabinet itself. Most of what Kjell does is making small boxes and baskets using traditional bentwood and sveiping, that is the stiching with birch roots that I first learned about in Voss. He is able to sell these at a local market that allows only local items made by hand. Kjell demonstrated sveiping to us and let me have a short length of birch root to play with back in the shop. To get the birch root myself I would have to go to a bog in the spring and dig it up.

After this visit, we went out of the town and up in to the mountains to find Olav Kvåle. Olav met us at the bottom of his steep and rough gravel road, where we transferred into his jeep. Olav is living a woodsman´s life in the forest. On the property, which has been in the family since around 1875, there are several small lafted cabins. The main house has been there for many years, and his parents always used it as a summer cabin, but since Olav moved up there in 1975, he has bought some other lafted cabins from other places and put them on the property. He says that it only takes about 3 hours to disassemble a lafted cabin, and about one day to reassemble it.

Olav is doing all of his carving in this place using hand tools and a little bit of router work. He has a small hydro and some solar pannels giving him power. Right now, he goes down to his father´s shop to use the machines for building the cabinets, but he is installing a generator so that he can eventually move the machines up to this mountain property. When there is snow, he is skiing in and out of the property. Olav lives by himself but often has guests and takes interns for several weeks at a time. Olav may well be the only person continuing to make this Orkdalskap right now. He has trained one German woman, and another from the Midwetern United States. Hopefully more woodworkers will visit him and carry on this tradition.

We had a very good afternoon relaxing with the Kvåles in the main house. I had some Norwegian moonshine in my coffee, the preferred mix. The moonshine is kept in a jug in the case of the grandfather clock for full effect.

Trondheim: Lademoen Kunstnerverksteder, starting August 6

The Lademoen Kunstnerverksteder is a big building in Trondheim that houses 34 professional artists´studios and space for 2 guest artists at a time. It was built as a school in 1906. I did not apply in time to take a formal residency here, but was able to rent the woodshop as a guest artist anyway. The woodshop is not necessarily what I would need to build furniture the way I am accustomed to at home, but has some major machines. For my purposes here, the only one I really care about is the nice big bandsaw. I brought a small box of hand tools from my own studio, and bought a few small Swedish knives along the way. After watching other people work for 6 weeks and seeing so many techniques, it was a great relief to have the keys to a woodshop for myself. Before I had aquired any wood to work with, I was eager to begin. I practiced with my new knives on a small scrap. I made a tiny strawberry and a spoony-looking thing with some shallow relief carving. I was just warming up and passing time until I could get started. Anyone want to buy a tiny wooden strawberry? Didn´t think so.

Everyone at Lademoen was very keen to make sure I was all set, had everything I needed, and would get something out of my stay. On my first official day, a Monday, one of the artists took me to find some wood. Her husband is the head of the industrial design department at the university in Trondheim, so we were able to go through the wood scraps and stores at that woodshop. I was not sure what I was looking for except that I wanted some natural curved peices and some fresh or at least air-dried pine. For a very small donation to the woodshop fund, I was able to get a couple of birch stumps that some eager student had abandoned, a halved log of pine, and a random selection of other sticks that would give me some options.

Back in the woodshop, I began to dissect the stumps on the bandsaw, slicing away to untangle several distinct curved pieces where the trunk spread into the roots. These were the building blocks I was playing with as I started imagining shapes, and also started trying to puzzle these curves into forms I had already imagined. I´ll tell you what I´m building when I see what I´ve done. I´ll tell you one thing . . . it isn´t furniture!

Everyone at Lademoen was very keen to make sure I was all set, had everything I needed, and would get something out of my stay. On my first official day, a Monday, one of the artists took me to find some wood. Her husband is the head of the industrial design department at the university in Trondheim, so we were able to go through the wood scraps and stores at that woodshop. I was not sure what I was looking for except that I wanted some natural curved peices and some fresh or at least air-dried pine. For a very small donation to the woodshop fund, I was able to get a couple of birch stumps that some eager student had abandoned, a halved log of pine, and a random selection of other sticks that would give me some options.

Back in the woodshop, I began to dissect the stumps on the bandsaw, slicing away to untangle several distinct curved pieces where the trunk spread into the roots. These were the building blocks I was playing with as I started imagining shapes, and also started trying to puzzle these curves into forms I had already imagined. I´ll tell you what I´m building when I see what I´ve done. I´ll tell you one thing . . . it isn´t furniture!

Trondheim Museums, August 3 & 4

Sverres Borg Trondelag Folkemuseum consists of old buildings and houses collected from this region of Norway set on the grounds, as well as an exhibit of artifacts and objects from Norwegian daily life from the 1700´s to present. The stave church here had these big bulb shapes at the bottoms of the staves. There was some influence from Russia being blended with the building style. Inside the houses were the typical Norwegian objects including mangles and small chairs made grom natural curved wood. Most objects as well as the carving and painting in a house would have been done by the farmer himself. Most of the timber buildings are small, one or two rooms and often serving single functions so that the farm consists of a dozen small buildings. One of the houses was from a wealthy farmer who liked to entertain, and the ceilings were richly painted by hired artisans. I really liked one table in this house. Its 2 drop leaves fold down so that the table becomes about the size of a sawhorse. Perhaps it is not uniquely Norwegian, but clever. Inside the exhibit, there were several Empire sleds like the ones I saw back in Lillehammer.

The Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrialmuseum collection includes historical examples of material culture and decorative arts, as well as contemporary crafts, including some Wegner chairs and a piece (not pictured) by the late Peter Voulkas (whose wife and son are my neighbors and landlords). There was a special exhibit of crowns from around the world. They ranged from standard Burger King looking German crowns to very exotic headdresses from South America. The typical Norwegian bridal crown is made of very thin metal, and I would like to make one from all of the different beer cans from Norway. Queen of Beers.

The Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrialmuseum collection includes historical examples of material culture and decorative arts, as well as contemporary crafts, including some Wegner chairs and a piece (not pictured) by the late Peter Voulkas (whose wife and son are my neighbors and landlords). There was a special exhibit of crowns from around the world. They ranged from standard Burger King looking German crowns to very exotic headdresses from South America. The typical Norwegian bridal crown is made of very thin metal, and I would like to make one from all of the different beer cans from Norway. Queen of Beers.

Outside Trondheim: Stadsbygd, August 2

Back to Kirkenes, July 29 & 30

Svanvik, July 28

Kirkenes to Karasjok, July 22-27

Tromsø, July 21

Målselv, July 20

After 11 hours on the Hurtigruten, we arrived in Finnsnes and took a bus to Målselv to visit one of Norway´s experts on traditional woodcraft, Roald Renmælmo. Siv, Roald´s girlfriend who is also expert in traditional woodcraft, picked us up from the bus and took us to the property in the woods. Roald has been working with the NHU to preserve and document different types of woodworking traditions in Norway, including the making of a particular old type of reindeer sled called a pulk. Roald had the pulk that Nils Nilsen Anti had just made as part of this documentation project, so I was able to look closely at the pulk. (Nils is in his 80´s and is probably the last living Sami pulkmaker, but I will tell you all about him in a later entry.) When we arrived, Roald, Siv, and Siv´s brother had just spent nearly 2 weeks stripping birch bark off the birch trees and stacking it in flat sheets to store it. They had filled a whole shed with birch bark. There is only about one month in the year when the birch bark is loose on the tree, and this is when it must be harvested. A vertical slice is made through the bark with the knife, and then cuts are made all the way around the tree at the top and bottom of this slice, so the sleeve of bark is unpeeled in a square sheet. The bark is used to make some small items like baskets, but the big use for Siv and Roald is in constructing tradidtional sod roofs on traditional wood houses. The birch bark is the waterproofing layer that goes between the roof planks and the sod. It is incredibly effective. Roald and Siv have taken apart roofs and found that after 100 or more years, the uppermost layer of bark may be weathered, but the next layer of bark is as good as new.

Roald knows an incredible amount about working with an axe to cut and shape wood for cabins. He is extremely knowledgable in most of these old tools actually. I bored a few holes using a few of Roald´s old tapered auger twist drills, or "navar". These simple, T-shaped, hand-driven augers are typical in old norsk woodcraft, and some were even found on the Oseberg ship excavation so they were over 1000 years old. Roald prefers the navar to crank drills because they are so fast and simple. He has found the one and only blacksmith who is still making navar, Johannas Fosse.

Into these holes, one would drive a wooden peg or nail. This is called "nagling". Using a knife, a nail is cut from pine. It should be the heartwood of the pine, from the lowest meter of the tree so it has more give and won´t crack. The nail is driven into the hole and out the other side. The point of the nail is then split with the knife, and a tapered piece of wood is driven into the endo to the nail, wedging it open in the hole. Both sides can be sawn off clean. In the next week I would be going to visit the pulkmaker Nils Nilsen Anti, who is a master of this nagling, so I was glad to have a preview.

The next tools to try were the axes, so Roald set up a big log for me to hack away. Roald demonstrated how clean and straight he could cut the face of the log with his axe technique, and it looked very easy. I was ready to get rid of my machines and get a few axes until my turn. I was not so coordinated and it was very hard work. There is a video of me doing this that must be destroyed. I need some more practice. Still, it is amazing how much one can do with only an axe and a knife, and how quickly it can be done too. It makes machines seem too fussy.

Terri and I stayed all day and overnight with Siv and Roald and had a great time.

Roald knows an incredible amount about working with an axe to cut and shape wood for cabins. He is extremely knowledgable in most of these old tools actually. I bored a few holes using a few of Roald´s old tapered auger twist drills, or "navar". These simple, T-shaped, hand-driven augers are typical in old norsk woodcraft, and some were even found on the Oseberg ship excavation so they were over 1000 years old. Roald prefers the navar to crank drills because they are so fast and simple. He has found the one and only blacksmith who is still making navar, Johannas Fosse.

Into these holes, one would drive a wooden peg or nail. This is called "nagling". Using a knife, a nail is cut from pine. It should be the heartwood of the pine, from the lowest meter of the tree so it has more give and won´t crack. The nail is driven into the hole and out the other side. The point of the nail is then split with the knife, and a tapered piece of wood is driven into the endo to the nail, wedging it open in the hole. Both sides can be sawn off clean. In the next week I would be going to visit the pulkmaker Nils Nilsen Anti, who is a master of this nagling, so I was glad to have a preview.

The next tools to try were the axes, so Roald set up a big log for me to hack away. Roald demonstrated how clean and straight he could cut the face of the log with his axe technique, and it looked very easy. I was ready to get rid of my machines and get a few axes until my turn. I was not so coordinated and it was very hard work. There is a video of me doing this that must be destroyed. I need some more practice. Still, it is amazing how much one can do with only an axe and a knife, and how quickly it can be done too. It makes machines seem too fussy.

Terri and I stayed all day and overnight with Siv and Roald and had a great time.

Lofoten Island, July 13-20

After 3 weeks of going a new place almost every day, I was ready for some down-time. Lofoten Island is not a typical island vacation. . . . that is to say, it is not a tropical, beach getaway. Lofoten is quite famous and popular with artists because of its special scenery and light quality. It consists of sharp mountains jutting up off the sea, and is quite a bit above the arctic circle, so there are many weeks of midnight sun in the summer, including durning the week I would be there.

Terri McFarland and I flew from Oslo to Bodø, and then took the passenger ferry, the hurtigbåt, to Svolvær on Lofoten. We had not much to see but hours to kill in Bodø, so we bought some Norwegian wool yarn and Terri reminded me how to knit. The boat ride was very rough. The steward made everyone in seats towards the bow move back into the belly of the boat because it was so rough. The boat, large as it was, would dip beneath the horizon in the giant troughs between the waves. Not my favorite, but Terri, a film major at NYU for a while, was busy trying to get video documentation at the windows while also trying not to get knocked over by the bumps.

We both had rooms at the Lofoten Kunstnerhuset, a big house with rooms and artist studios in Svolvær. Terri was looking forward to some outdoor landscape painting. I was looking forward to sitting down and reviewing my notes and making some drawings. I got the better end of the deal because it rained the whole time. Nonetheless, Terri was quite happy because the artist studios on each end of the house had banks of windows on 3 sides, so from our hill she had a 360 degree view to paint from, though it was grey. One of my favorite things about Lofoten was the way the grass would spill rom the big cracks in the boulders and bedrock, these thin wedges of meadow sandwiched in. Terri, being a landscape architect and avid gardener, loved the fact that meadows seemed to crop up in every possible patch of ground and sod roof of Lofoten, and she especially liked quizzing me on the names of the wildflowers. As for the midnight sun, we only got midnight rain and midnight fog. It never got very dark though, so it could be just the same view at noon as at midnight.

On July 17, we went to Strønstad on the other side of the island to visit a local, widely known, Norwegian woodcarver, Arthur Johansen. Arthur and his wife Thune(?) live at a beautiful small bay facing the northeast, the direction of the midnight sun. Arthur was very welcoming. In fact, he drove into town about 40 km to pick us up. He showed us all around his wood carving shop. He makes some tourist trinkets, but also makes many commissioned picture carvings showing scenes from the sea and from people´s lives for commemorations. He and his wife had us over in the house for several hours. They really wanted us to try dried salt cod, the thing that drove (drives?) Lofoten´s economy. It is dried in the winter on giant A frame racks outdoors. It is so tough and fiberous, it is not easy to yank off a little strip. Then it takes an endless amount of gnawing to soften it and get it down. It took me about 5 minutes to consume the tiny sliver I agreed to eat. It was like purgatory chomping this tough string that tasted like low, low tide. I had quite a bit of coffee and water after, but couldn´t quite shake the taste. It was great fun visiting Arthur nonetheless. We stayed until around midnight, still hoping to see the midnight sun. There was a beautiful pink glow behind the clouds close to midnight. Our hosts showed us lots of pictures of both midnight sun and the winter´s norther lights to show us the effect of the famous Arctic light.

Otherwise, I had a nice week of walking, drawing, reading, baking, and knitting. We took the famous coastal steamer, the Hurtigruten, for one all-night stretch from Svolvær to Finnsnes. Going up through the fjords we had some amazing scenery, and again something close to a midnight sun with a brilliant 2 am dawn. It was not so great for sleeping because we were deck passangers, meaning no cabin.

Terri McFarland and I flew from Oslo to Bodø, and then took the passenger ferry, the hurtigbåt, to Svolvær on Lofoten. We had not much to see but hours to kill in Bodø, so we bought some Norwegian wool yarn and Terri reminded me how to knit. The boat ride was very rough. The steward made everyone in seats towards the bow move back into the belly of the boat because it was so rough. The boat, large as it was, would dip beneath the horizon in the giant troughs between the waves. Not my favorite, but Terri, a film major at NYU for a while, was busy trying to get video documentation at the windows while also trying not to get knocked over by the bumps.

We both had rooms at the Lofoten Kunstnerhuset, a big house with rooms and artist studios in Svolvær. Terri was looking forward to some outdoor landscape painting. I was looking forward to sitting down and reviewing my notes and making some drawings. I got the better end of the deal because it rained the whole time. Nonetheless, Terri was quite happy because the artist studios on each end of the house had banks of windows on 3 sides, so from our hill she had a 360 degree view to paint from, though it was grey. One of my favorite things about Lofoten was the way the grass would spill rom the big cracks in the boulders and bedrock, these thin wedges of meadow sandwiched in. Terri, being a landscape architect and avid gardener, loved the fact that meadows seemed to crop up in every possible patch of ground and sod roof of Lofoten, and she especially liked quizzing me on the names of the wildflowers. As for the midnight sun, we only got midnight rain and midnight fog. It never got very dark though, so it could be just the same view at noon as at midnight.

On July 17, we went to Strønstad on the other side of the island to visit a local, widely known, Norwegian woodcarver, Arthur Johansen. Arthur and his wife Thune(?) live at a beautiful small bay facing the northeast, the direction of the midnight sun. Arthur was very welcoming. In fact, he drove into town about 40 km to pick us up. He showed us all around his wood carving shop. He makes some tourist trinkets, but also makes many commissioned picture carvings showing scenes from the sea and from people´s lives for commemorations. He and his wife had us over in the house for several hours. They really wanted us to try dried salt cod, the thing that drove (drives?) Lofoten´s economy. It is dried in the winter on giant A frame racks outdoors. It is so tough and fiberous, it is not easy to yank off a little strip. Then it takes an endless amount of gnawing to soften it and get it down. It took me about 5 minutes to consume the tiny sliver I agreed to eat. It was like purgatory chomping this tough string that tasted like low, low tide. I had quite a bit of coffee and water after, but couldn´t quite shake the taste. It was great fun visiting Arthur nonetheless. We stayed until around midnight, still hoping to see the midnight sun. There was a beautiful pink glow behind the clouds close to midnight. Our hosts showed us lots of pictures of both midnight sun and the winter´s norther lights to show us the effect of the famous Arctic light.

Otherwise, I had a nice week of walking, drawing, reading, baking, and knitting. We took the famous coastal steamer, the Hurtigruten, for one all-night stretch from Svolvær to Finnsnes. Going up through the fjords we had some amazing scenery, and again something close to a midnight sun with a brilliant 2 am dawn. It was not so great for sleeping because we were deck passangers, meaning no cabin.

Sunday, August 13, 2006

Flam to Oslo, July 10-13

There was some question as to how I would get from Urnes to Flam in time to catch my train back to Oslo. Flam was on the other side of the fjord from Urnes, and the ferry did not start running quite early enough to make all of the right bus connections. Ian´s idea was that I would help Dave, his partner, get the 2 tandem kayaks back across the fjord by piling all of my luggage into a kayak and paddling across very early the next morning. This plan was exciting, of course, but made me a bit nervous. Paddling 2 or 3 kilometers in the rain with all my luggage sounded like a potential catastrophe, but also like a great story to tell afterwards.

It turned out that Dave was not able to make this journey on this particular day, so I was just going to have to miss my train and take the next one later in the day. Probably for the best.

I took the famous Flam railroad on a steep ascent from the fjord to the high plateau at Myrdal, where the train from Bergen to Oslo would pass. This Flam railroad is a tourist attraction because of its very steep ascent and spectacular scenery.

Back in Oslo, I was meeting up with my friend Terri McFarland, a landscape architect and landscape painter from San Francisco. We were to travel up to the arctic circle together for a week of painting and drawing, but first we had a few days in Oslo. I was able to return to my favorite spots, the Viking Ship Museum, the Folk Museum, and Vigland Park, and to recapture some of those lost photos from the first few days of my trip. It was great to see the Viking ships again after spending time with several boatbuilders.

It turned out that Dave was not able to make this journey on this particular day, so I was just going to have to miss my train and take the next one later in the day. Probably for the best.

I took the famous Flam railroad on a steep ascent from the fjord to the high plateau at Myrdal, where the train from Bergen to Oslo would pass. This Flam railroad is a tourist attraction because of its very steep ascent and spectacular scenery.

Back in Oslo, I was meeting up with my friend Terri McFarland, a landscape architect and landscape painter from San Francisco. We were to travel up to the arctic circle together for a week of painting and drawing, but first we had a few days in Oslo. I was able to return to my favorite spots, the Viking Ship Museum, the Folk Museum, and Vigland Park, and to recapture some of those lost photos from the first few days of my trip. It was great to see the Viking ships again after spending time with several boatbuilders.

Urnes, July 8 & 9

The two busses that went from Dale to Songdal via Forde took the better part of the day on July 8. Ian Karl, brother of my friends the Karl sisters in Oakland, picked me up in Songdal. He is a partner in a sea kayak and whitewater guiding operation on the Sognfjord in the summers, and timber framing in Wisconsin in the winters. He was on a mission to pick up a flock of kayaks at a drop off point up the fjord and bring them back to the home base, so we were many hours in the van on some steep and windey mountain roads. There were some amazing views, including one of the biggest rainbows I ever saw. At the pick up spot, there was an old, water-powered saw mill, which was interesting to explore.

Ian lives up the road from Norway´s oldest stave church, Urnes Stave Church. On July 9, I walked and hitched (everyone knows each other in this town, so it was perfectly safe, Mom) down to the end of the road. Before going up the hill to the church, I made a side excurion and took the ferry across the fjord to Solvorn to see an exhibit at the Galleri Walaker. A friend of a friend, Mari Ormberg, has just finished her Masters degree in traditional woodworking at the folk arts school in Rauland (Southern Norway), and was having an exhibition at this gallery. She is using traditional carving techniques to make abstract, contemporary relief works that hang on the walls like paintings. Nice stuff, and nice to see someone using traditional methods in a new way.

The ferry returned me to Urnes, where I went up the hill to the church. Urnes stave church was built in the 1100´s, and is quite small and simple. Stave churches are built much like the grindbygg constructions I saw a few days before. The whole building is suspended on the main pillers of upright wood logs, the staves. There is some very intricate carving on the portals of the church. The story it tells is from old Norsk mythology, so they were mixing this with Christianity when Christianity first started to stick in Norway.

Saturday, August 12, 2006

Dale, Hyllestad, and Flekke, July 6 & 7

On July 6, I took the "fast boat" from Bergen to Rysjedalsvika on the north side of the mouth of the Sognefjord, Western Norway´s biggest fjord. I was staying at the Nordic Kunstnersenter at Dale, an artist residency center that hosts mainly artists from the Nordic countries. The director, Elisabet Gunnarsdottir, was very helpful and let me rent a room there for a few days. It is up above the town, so I had a beautiful view of the fjord.

On July 7, Ove Losnegard picked me up at the center and took me to work with him. Ove is a director at Jensbua, a foundation in Norway that is involved with the preservation of cultural heritage. At this time, the project Jensbua was working on was the construction of 3 new buildings for the millstone museum in Hyllestad. The buildings, 2 small and one large, are constructed using the ancient "grindbygg" technique. Timber post, "stav", and beam ,"bete", corners are braced by crossbeams, "broddeband". The frames form gate-like parts, the "grind", thus the term "grindbygg". These gates are raised up, (like in the Amish barnraising seen in the movie "Witness" with Harrison Ford), A beam, the "stavleie", lays across the tops of the gates connecting them, and then the roof beams, "sperr", are placed with corner frame joints at the peak. Then a plank roof is put on, followed by several layers of birch bark, topped with sod. This place used to be where millstones were produced and exported throughout Northern Europe. The millstones were cut directly from the bedrock of soft micaceous schist. Hundreds of these millstones, which would be used for grinding grains, are still scattered around the forest area at the museum site. The foundations of this post and beam, timber-framed building are usually a few flat rocks under each post, but here they have used some spare millstones. I do not recommend this type of foundation for California constructions . . . not to code!

The forest surrounding this site is so lush with a mossy and fern covered floor, that if I were to see a gnome during my travels, it would have been here. Now on the lookout for natural curved wood and in the forest, I saw many examples of the curves I had been learning about in Bergen.

It was great to watch Ove and his 2 helpers at work. This whole building can go up with only a few workers and very little noise. Ove and one helper were on the roof most of the day, fitting the tennons into the mortises on the corner frame joints at the roof peak. When something wasn´t going together right, Ove got out his chisel and fixed it up.

I can see why this type of construction has lasted for thousands of years in Norway, and why buildings nearly one thousand years old are still standing. The building is not tied into the ground at all. The foundation is basically non-existant. The whole building is instead self-supporting, made like a piece of furniture so it acts as a unit, like a box sitting on the ground.

After work, Ove drove me to the Jensbu building near the town of Flekke. We were looking at the last Jensbua project, a boat called Bakkejekta. Many of the carpenters and boatbuilders I had met in Norway had been visiting Jensbua in the spring in order to help work on this boat, built by hand with traditional methods. Bakkejekta first sailed on June 23 this year and is a beautiful boat.

Friday, July 07, 2006

Os, Lyse Kloster, & Fana, July 5

I was on the 8 am bus to Os about an hour south of Bergen to see another traditional boatbuilding workshop, the Oselvarverkstaden (Oselvar Boat Yard). I circled the building a few times because it seemed pretty still, but then a door opened. There are three apprentice boatbuilders there now, and they are each making a færving. The Oselvar færving that is being built here is very close to the Hardanger færving being built at the Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter in Norheimsund. In fact, these four-oar rowing and sail boats are very close to the ones found in on the Gokstad Ship in the Viking burial mound from the 9th century. This structure has been used for over one thousand years, and there are archeological findings of parts of these same clinker built boats up to 2000 years old.

Now they use machines to speed up certain processes, but depend largely on hand tools, especially the axe, for the most part. When they are making the "T" shaped keel out of oak, they are now making an undercut on the tablesaw at a 12 degree angle. They waste out the part under the arms of the "T" by overhanging the stick on the jointer and rabbetting out the waste. Slick trick! Get that darned guard of the jointer people!

But being a builder of traditional wooden boats in Norway still means taking a lot of care and patience in wood aquisitionand selection. We thought we took our time at College of the Redwoods, pulling every choice plank out of the wood room and carefully inspecting the color and grain figure. This is different though. They spend about 2 weeks every year up in the forest looking at trees that have the right curves, and ones that are old, slow grown, wide trees that can provide them with the very broad and tight-grained planks needed to make a boat with just 3 strong strakes. The trees are milled with a portable saw mill and the wood is brought to the boathouse. Most of the boat is pine, but the parts used for the stem and stern and keel are oak. The oak is put into a pen under the dock. It will sit there for three years, underwater when the tide is high. The Air exposure during low tide protects the wood from getting attacked by shipworms. After three years, the oak is more soft and workable, and much of the tension has been released so that the oak is very stable. It is then air dried for another year. A lot of space is dedicated to wood storage here.

Both of the apprentices working on their boats that morning were in the middle of their boats, so I could really see the process. Berit Osmundsen, a woman from the Lofoten Islands, was finishing shaping the halsen with a hand plane. Maik Riebort, a man living in Berlin who is also a film student and a dancerwhen he is not a boatbuilding apprentice in Norway, was making the flatter boards that join up the halsen. He said this is the easiest part in the whole boat.

I love seeing how the boats are built in place, and how they are braces and fixed in place with sticks from the floor and low ceiling beams pushing the boat planking into tension and compression. With this system, the builder had a lot of fine control over the exact angles and shapes the boards take. It is very practical and effective, and they do not have to sit around doing trigonometry on thier calculators (as I am prone to do).

OK, that's it! I'm becoming a boatbuilder! Get me an axe!

Another reason to become a Norwegian woodworker: the blue pants. All of the carpenters wear them here, sort of like Carhartts. But these have all of these auxillary pockets like wearing an apron, plus they have these foam insert knee pads. I told Berit that I had to have some blue pants. She happened to have a pair left by an ex-boyfriend that were the right size and price for me. We just had to find a ride to her house.

Luck would have it that a retired gentleman had stopped by for lunch. He often came to the boathouse for a little society around lunchtime. He was wearing no shirt and ratty pants. He had been fishing all morning and had four or five big fish with him. He really wanted to give me one, but I thought better of it considering I was doing a lot of riding on the bus and it was quite hot out. The man, Andor, gave us a ride to the blue pants. He thought it was a shame that I should have to take two busses and do some backtracking in order to get to my next stop, Fana, so he offered to drive me to another stop.

Well, he spoke very little english, and I speak very little norsk. I tried to understand the plan, but ended up just saying "OK" a lot. We stopped at some ruins at Lyse Kloster that are dated 1146. These are fantastic, but they are not in either of my guidebooks. Andor ransacked his cluttered car for a brochure for me while I climbed up the low, fat walls of the ruins and hopped over doorways. Like other places I have been outside the States, the ruins were no more protected from me than I was from them. That's much more fun. Some of my favorite parts were the places in the stone walls where the rack sizes were mixed up, so there would be a lot of small, flat raock and then a patch of rounded cobbles mixed in.

The only other folks around were a woman and her school-aged son. By the time I had returned from taking pictures and exploring, Andor had stuck up a conversation with this woman. He managed to get her to take a fish home.

Andor is quite a character. He is enthusiastic, friendly, generous, chatty, and hard to shake. He is a free spirit, so he sometimes drives on the right side of the road, but he likes to mix it up by driving in the middle and on the left too. The gutter is not off limits either. Between his driving style and his interest in showing me the region, I wondered if I would get to the museum where I had an afternoon appointment. But Andor did deliver me to Fana and the Horda Museum, right to the front steps. He drove right through the detour tape that had been strung tight across the road to do so. He seemed to know the people here too. He came into the museum with a warm bottle of beer and procured 2 glasses from the cafe. He still had no shirt on, by the way. We split the beer. He explained that it was the same temperature as our bodies, which was a good thing so that we would not go into shock. Right. Andor stuck around for quite a while making new friends even after I took off with the archeologist, Ole Mikal Olsen. I won't soon forget Andor.

The Horda Museum in Fana had an interesting object that I really liked: a fish coffin. It is a boat shape with open slits and a lid. It would hold live fish that fishermen were towing back to the market. The main thing that the Horda Museum houses is a large collection of old boats in storage sheds. Ole is very knowledgable about the history of these boats, and he took me around to see them. These boats were again quite similar to the ones I had seen at the boatyards, but some of these were with more pairs of oars, up to 10 oars (ti-ærving). Ove told me that in the oldest boats found, instead of having iron clinkers holding the planks together, they were actually tied with roots.

Some of the boats in the Horda collection had been used for fishing, but others had been church boats used only to go to church. These were very finely crafted with small details, and they were in mint condition due to their low milage.

Bergen, July 3-4

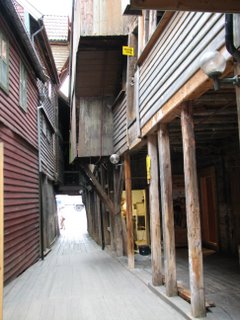

Monday morning I was ready to see more stuff. I headed to the old town part of Bergen, the Bryggen.

Monday morning I was ready to see more stuff. I headed to the old town part of Bergen, the Bryggen.This is a city block of old buildings right along the harbor that were originally built in the 12th century. The buildings were the center of the fish trade, which was tightly controlled by the Hanseatic Leauge of German merchants until the 1700s. The buildings of the Bryggen have burnt down several times over the centuries, and have been continuously rebuilt in the same way. The current structures were last built in 1702, and are being restored and preserved currently.

Alf Isak, Silje's good friend, is an architecture student in Bergen who is making the woodworking demonstrations and giving public tours in the Bryggen during the summer, and another one of their friends, Jacob, is one of the woodworkers restoring the buildings. Alf and Jacob taught me all about the old construction methods still being used here today. The restoration work is necessary because some of the pine of the building and foundations is decomposing. The rebuilding is being built almost entirely with the same types of tools and techniques as the original buildings were in 1702.

The buildings are almost entirely made of pine. The construction method is another traditional Norwegian method called "lafting". Lafting is very different than the "grindbygningen" technique I learned about in Voss. Not to simplify it too much, but lafting is more like Lincon Logs where the logs are interlocked at the building corners. The sides are hewn of a whole log with an axe to make one thick plank, a laft. This 5-6 inch thick plank includes the heartwood and the pith of one log, so it is very stable. As Alf will demonstrate, to hew the log, first notches arechopped down the length of the log, then the remaining wood is lopped off. The ends get an edge lap/ bridal joint. The work is almost entirely done with an axe; it can be very quick and accurate for a skilled worker.

There is a great trick for getting a tight fit between the lafts as they are stacked on top of each other lengthwise. After the sides are hewn off the logs, the top and bottom edges of the laft are beveled on both sides with a drawknife so that they have a pointed edge. When one laft is stacked above the last one, they rest point to point. A forked, double pronged scribe called a "me" is used to "medrag" or scribe a double line: one line on the upper laft, one on the lower. The two lines are parallel, so even though the surface will not be a flat plane, the two surfaces will match up if both lafts are trimmed to the scribe lines. I need to get me one of these medrags for all of my fitting a curve to a curve work!

Looking around, I noticed that the natural forms of curved wood were constantly being used here too. In grindbygningen, the curved parts cross brace the upright and the horizontal beams. In lafting, the point where the trunk widens and spreads into the roots is used as a corner block to support the external walkways or gangplanks cantileivered around the buildings. This particular part of the tree is called the knee of the tree, and a lot of tree's knees are being used in Bryggen.

After work, Alf joined me for a pint (.45 liters actually, a norsk pint). I think he deserved it after all of that chopping. It made me thirsty!

------------------------------------------

The Fourth of July was on a Tuesday. Seeing as it was a holiday, I slept in and spent a late morning at a cafe writing postcards. At 11:00 am I was having a coffee, but most of the people on the patio were having their norsk pints already. I guess everyone was having a holiday. I kept waiting for the city to set up bleachers and parade route detours next to the harbor, but that never happened. I visited Alf and Jacob at Bryggen again to see some more chopping. I really admire hard work; I could watch someone work hard all day long. (I can't take credit for that one, but I can't recall to whom I should give the credit.) Actually, I wanted to show them Kåre Herfindal's book which they had not seen yet. We were being wood geeks together.

In the afternoon, I visited the Vestlandke Kunstindustrial Museum. I was hoping to see some great examples of traditional or typical Norwegian wood furniture. There was a collection of period furniture with some contemporary stuff mixed in, but nothing in that exhibit grabbed me. What did catch my attention was the Chinese sculpture exhibit. I really liked the attitude and posture on this one warrior . . . sort of knock'um sock'um.

Well, I had pretty much done everything I wanted to do in Bergen. I had been hearing the Irish pub through my bedroom window for several days, and I decided it would be a good place for me to do some individual celebration of the Fourth. Skål everyone!

Bergen, July 2

I stayed at a friend of a friend's girlfriend's apartment in Bergen. The place is really centrally located across from the theater. It is upstairs from a falafel place and across form and Irish pub that stays very noisy until 3am. It was great to be in an apartment and have a kitchen! Thank you Silje!

I stayed at a friend of a friend's girlfriend's apartment in Bergen. The place is really centrally located across from the theater. It is upstairs from a falafel place and across form and Irish pub that stays very noisy until 3am. It was great to be in an apartment and have a kitchen! Thank you Silje!After all that I had already seen and learned, my brain was full. I spent half of Sunday wandering around Bergen like a zombie. There was a museum on my agenda, but I couldn't bear to be inside. I took the Fløibanen, the funicular railroad, up to the top of the hill and took in the birds, eye view of the harbor and the town. Bergen is a university town and a harbor town. It is a hairpin of a harbor, stretching deep and narrow right to the town center. An outdoor market with loads of fish is open everday right at the point of the harbor.

Not much else is open on Sundays in Norway. I strolled the main pedestrian street window shopping and noticing the street performers. The horn ensemble that does instrumental renditions of "Blue Moon", "When I'm 64", and "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina" is pretty darn good. The most impressive is the guy on the wood xylophone that does the full orchestral version of the theme to "Star Wars". Here are some photos of Bergen at 10:30pm (midnight sun).