Thursday, July 06, 2006

Voss, June 30 - July 1

I happened to arrive in Voss in the midst of Norway's "Extreme Sport Week". That was obviously not what I had in mind . I got of the bus woozy and hot to find the banks of the fjord crowded with tents, college students, and parachute landing sites. In the tourist office, there was a group of American guys claiming to be making a TV pilot episode and trying to find out where they could get a whole sheep's head to eat. Nice.

That night as the porch and the lobby filled with college aged kids holding bags of beer, I was having my doubts. I wondered what I was doing in Voss. I wondered what I was doing in general that had me staying in a youth hostel dorm room. The first question was answered when I got to see who and what I was there to see the next day. (The second question still stands.)

After my scandinavian smorgasbord breakfast at the hostel, I headed up the hill to the Magnus Dagestad Museum. Magnus Dagestad (1865-1957) was the star student of Lars Kinsarvik (Lars from yesterday, remember?) Magnus Dagestad, like Lars Kinsarvik, embraced the idea of developing and promoting the new style of Norwegian folk art. He mainly made furniture that was either carved, or painted in the tradition of Norwegian rosepainting (his wife was conveniently a skilled rosepainter), and some of his work was both carved and painted. The patterns seem in between the structured graphic quality of celtic knots and the organic flowing quality of art nouveau. The figures seem pretty contemporary in style based in modern, clean shapes.

Next on the agenda was the real reason I came to Voss: finding Kåre Herfindal, an expert on the many wood traditions of this region in Norway. I had had only the briefest phone call with Kåre the day before. Maybe it was a language barrier. This time I tried speaking Norwegian.

"Hei Kåre! Jeg heter Ashley. Hovrdan har du det?" Hi Kåre! My name is Ashley. How are you?

He said fine.

"Kan jeg kommer til ditt hus nå? Jeg vil gjerne se lagging og sveiping."

He said "Ja" I could come to the house.

"Det er bedre å komme i taxi eller å gå?" When I asked him if it was better to come in a taxi or to walk, he started speaking in perfectly good english and said he would come get me in his car. It turns out that he didn't realize that I was the same person that had been emailing him; he was expecting a man.

Kåre Herfindal has been teaching at the Vestnorsk Kultur Akademi. He is semi-retired, but it sounds like they won't let him quit. We went by the school workshop first where there were a few examples of student work left from the semester. These were small bentwood boxes that are made by "sveiping". These are a lot like the Shaker bent wood boxes, but instead of being nailed together, these are sewn together using the thin roots of birch gathered from a swampy bog where the tree roots are more exposed.

The traditional way to sew the boxes is to sew them right where the two ends overlap, sewing perpendicular to the grain. He and his students have begun to push this tradition with some more modern, curved edge ends to the boards with curved stitch patterns following those edges.

Right next door to the school workshop is the Vestnorsk Kultursenter and Kulturmagasinet where 15 artists/craftspersons have a common workshop. One of those craftsmen is an englishman named Keith Barker. Keith is an exuberant chairmaker and he was working that Saturday. Keith tries to keep his chairs strong and light by having the back leg come up at an angle to the chair. He had a really clever jig for gluing up a chair side that is great if you have a lot of different angles in a single plane. Keith says "Hello" to Wendy Mayumara and to Garry and Sylvia Bennett. I am encouraging Keith to join the Furniture Society.

Keith and Kåre looked at some pictures of my work. This sparked an interesting discussion about whether my work was particularly American. Keith thinks that to get away with making the kind of stuff that I make, it is very advantagous to be an American woodwork, unbound by tradition, in an American market with more open-minded and decisive buyers. It is hard enough to pedal studio furniture, but apparantly it would be harder in Europe. Keith feels that the audience would be confused by objects that are to far from the roots of a tradition. Well, that's the first good thing about being American so far! Keith has a point. Look at how the students and Kåre have pushed the tradition of sveiping. It is still 99% grounded in the classic form. I told Kåre maybe someone could really push sveiping by using that technique in a cabinet or something. He said "Maybe you!" and we all had a laugh.

There were some examples of "lagging" at the school too. Lagging is like coopering, using staves to make a barrel. These are tapered cone sections, and are used for beer barrels and pitchers. The most interesting part is the way they are held together by a hoop made from a plyable root or branch that has notched scarf joints cut in the ends. The hoop locks together, and then cinches itself tighter as the hoop expands from being shoved down the tapered cone. This might be difficult to visualize, sorry!

Kåre showed me a building on the grounds that has been constructed in the traditional "grindabygg" technique. Archeological sites show evidence of this type of construction going back 4000 years. Talk about tradition! This is a post or frame type of construction. There are corner braces made from naturally curved pieces of wood. Having a curved brace instead of a straight piece at a 45 degree angle actually makes the house more durable by making it less stiff and more flexible in strong wind, much like how the curved parts make the wooden boats strong and flexible.

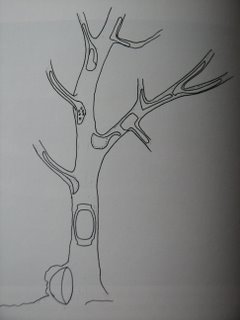

Kåre happens to also be an expert in "naturformer i tre", the natural forms in wood. The use of natural, grown curves in wood is pervasive in Norwegian woodworking. I am seeing it in the sleds, the boats, the buildings, and in small objects too. We went back to Kåre's house to see many examples of smaller objects from a tree's natural form. Bowls and øl kjenge would be made from the burl, while spoons, clamps, and all sorts of things can be made from the fork between the trunk and the branch.

One last very Norwegian technique that Kåre is (guess what!) an expert in is kolrosing. Kolrosing looks a bit like skrimshaw. A drawing is made by scribing into the wood with a knife. The fine line is nearly invisible until powdered birch bark is rubbed into the cut, darkening the lines. This is sealed with oil, and then sanded to knock down the burr from the knife cut. It would suck if you had accidently scratched the wood without knowing it, because those marks would show up along with the rest. It is like invisible ink being exposed. In fact, kolrosing is used on these joined wedding spoons. The spoons and the chain that links them together are carved from a single piece of wood and then inscribed with decorations. The decorations remain invisible until the bride and groom both eat pudding from the same bowl with these spoons, and the fat in the pudding darkens the lines. Presto magic!

Well, Kåre Herfindal is awesome and I now have his book, "Handverks-Teknikkar i Tradisjon of Fornying: Sveiping, Kolrosing og Bruk av Naturformer i Tre". It is written in ny-norsk, as if trying to read in norwegian wasn't enough of a challenge. I'm on page 2. Great photos though!